Another Premier League season, another campaign in which at least two of the three promoted teams have struggled.

Another Premier League season, another campaign in which at least two of the three promoted teams have struggled.

It’s becoming increasingly difficult for those that ascend from the Championship to compete on a level footing with the top-flight’s giants, and even established Premier League sides with smaller budgets are feeling the pinch – Burnley and Leeds United are staring the possibility of relegation in the face.

The concept of trying to create a level playing field is one that often gets discussed. That was one of the principles behind the introduction of Financial Fair Play (FFP) rules, although you wonder if those are worth the paper they are written on given the ‘creative’ ways in which clubs like Manchester City are able to navigate their way around the law.

Mind the Gap

As the gap between top and bottom of the Premier League widens, it’s worth looking at a competition where an enforced salary cap is in place – the USA’s MLS. Each team has a very defined limit on their spending, and transfer fees are essentially non-existent as each franchise opts to trade players with other clubs or buy in cheaply from South America.

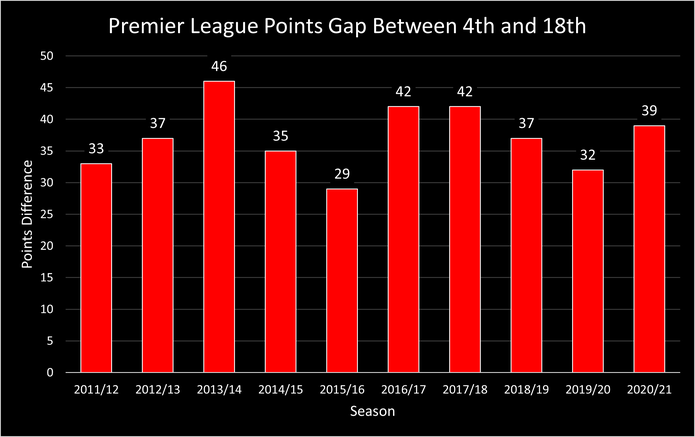

So let’s put it to the test. We’ve taken the points difference between the fourth placed team in the Premier League for the past decade, and plotted the points difference between them and the side that finishes 18th – i.e. top of the relegation zone.

While it’s far from the straight upward curve we were expecting, it’s still clear that – since 2016/17 – the gap between the fourth-placed team in the Premier League and the side that finishes third-from-bottom is widening….a classic case of the have’s and the have not’s.

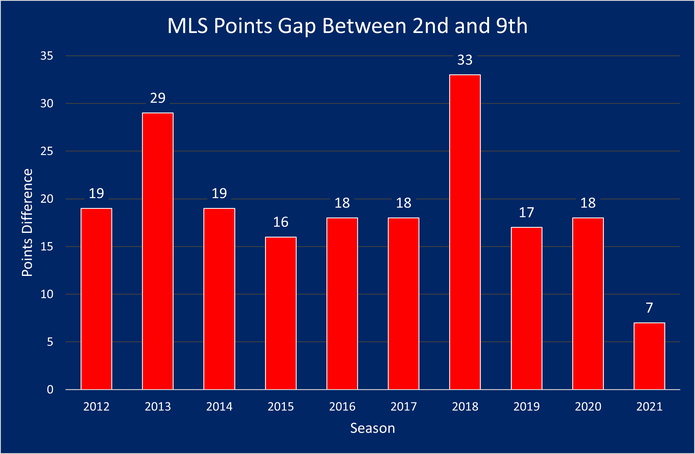

Let’s compare and contrast that to the MLS’s Eastern Conference. With fewer teams in the competition, this time we’re looking at the gap between second and ninth:

Aside from a couple of anomalies, look how stable the data is – in seven of the last ten MLS seasons, the gap between second and ninth has remained between 16-19 points, which shows that a salary cap fulfils the objective of making the division consistently competitive.

This is a small sample, of course, but it does hint that a salary cap closes the gap between the top and the bottom of the table, and makes football more competitive and entertaining as a result.

Should the Premier League Have a Salary Cap?

Here’s an interesting question: does anybody really care if the Premier League is played out on a level playing field financially?

Any GCSE level student can bore you rigid about free market economics, and the Premier League is this in action – supply (top-level players picked up from around the world) and demand (the ability of big clubs to pay huge transfer fees to secure them).

But do we really want a situation where the two finalists in the Champions League – Manchester City and Chelsea – have posted an annual loss of £1.5 billion (that’s not a typo) between them?

Maybe a salary cap is the answer, because right now we’re asking Norwich City (with an annual wage bill of around £100 million) to compete with Manchester City (around £360 million). They play each other and, lo and behold, City post 5-0 and 4-0 victories. Do we really want the beautiful game to become a series of matches where we know what’s going to happen before a ball has even been kicked?

When you add up all of the Premier League’s annual salary spend and divide it by 20 (the number of teams), the mean figure is around £190 million – only 5/20 teams pay more than this. So, imagine a scenario where they would have to offload players to meet a £190 million cap, while those clubs lower than the threshold could then pick up these stars given their extra wriggle room in the budget.

When you add up all of the Premier League’s annual salary spend and divide it by 20 (the number of teams), the mean figure is around £190 million – only 5/20 teams pay more than this. So, imagine a scenario where they would have to offload players to meet a £190 million cap, while those clubs lower than the threshold could then pick up these stars given their extra wriggle room in the budget.

It’s a redistribution of wealth, a redistribution of quality players and, as a result, a more competitive and equal Premier League.

When Carlo Ancelotti was the manager of Everton, he spoke publicly about the benefits a Premier League salary cap could bring.

“You have to have the weaker teams, stronger. That’s it. Give more power to the weak teams,” he said.

“The salary caps means less money for the manager, means less money for the players. But to try to equalise, a little bit, the competition I think it can be an idea. It can be a solution.”

And that’s also one of the problems: the players don’t want to have their earnings capped. A salary limit was set to be imposed on League One and Two in time for the 2021/22 season, but the players revolted and their union representative, the PFA, argued that it was ‘unlawful’. The Football League duly scrapped the idea after taking legal advice.

In the NFL, there’s a rigorously imposed salary cap of $182.5 million per season, and that’s to ostensibly ensure the financial integrity of the organisation. But it offers another benefit too – in the past ten seasons, eight different teams have won the Super Bowl. The salary cap, therefore, improves the competitiveness of the sport’s biggest prize markedly.

A salary cap will not stop the big clubs racking up hundreds of millions in debt, and it won’t stop Manchester City and co finding loopholes to get around such legislation. But it will prevent them from hoarding the best players, and make transfers like Jack Grealish’s £100 million switch from Aston Villa all the more unlikely.

Do we want to see a ‘fairer, more competitive Premier League? The answer probably depends on which club you have an affinity for.