It is, without question, the hardest steeplechase horse race on the planet, and so it comes as no surprise that the Grand National is also amongst the most dangerous.

It is, without question, the hardest steeplechase horse race on the planet, and so it comes as no surprise that the Grand National is also amongst the most dangerous.

Horses falling as they jump the mammoth fences, being dragged down by others and being pulled up by their jockey as the action gets too intense are all commonplace, and it’s sad to think that there has to be a Wikipedia page dedicated to fatalities in the famous race – that reveals that there have been sixteen fatalities in the race since the year 2000 from 914 (1.86%) entries. The average fatality rate in jumps racing is four per 1000 (0.4%).

The officials at Aintree have taken considerable steps to make the Grand National safer, but it is what it is – a four-mile slog, typically on soft or heavy ground, that features some of the most devilish obstacles in National Hunt racing.

What Prevents a Horse from Finishing the Grand National?

Occasionally, logistics prevent a horse from finishing the Grand National – the 1993 race was cancelled following an epic false start that saw 30 of the 37 declared runners tackle much of the Aintree course – seven even finished the 4m 2½f trip – despite the desperate efforts of stewards to wave them off.

Otherwise, there are four main reasons that a horse why a horse wouldn’t finish the Grand National:

- Falling

- Unseating the rider

- Brought down by another horse

- Pulling up

We might include a ‘refusal’ as well, when a horse just won’t jump over a particular fence, but these cases are pretty rare.

Since 1984, 311 horses have fallen in the Grand National, and that is as the name suggests – hitting the fence before falling, or slipping and sliding after correctly taking the jump and falling that way. Roughly 20% of National entries have fallen since that 1984 renewal.

We can include ‘unseated rider’ in this category, as the horse may stand upright after taking an obstacle but their jockey may hit the deck instead.

Then we have ‘brought down’, which as the name suggests is where a horse is taken out by another runner. It’s rare for horses to collide in mid air when jumping, and it’s usually on the other side of the fence upon landing where the most chaos occurs – a faller causing other horses to trip is a common occurrence.

And for some, the length of the Grand National course, or the fierce pace set, proves to be too much, and their jockey will pull them up and out of the race if they fear for the wellbeing of their animal or where it’s plainly evident they are out of contention.

How Many Horses Finish the Grand National?

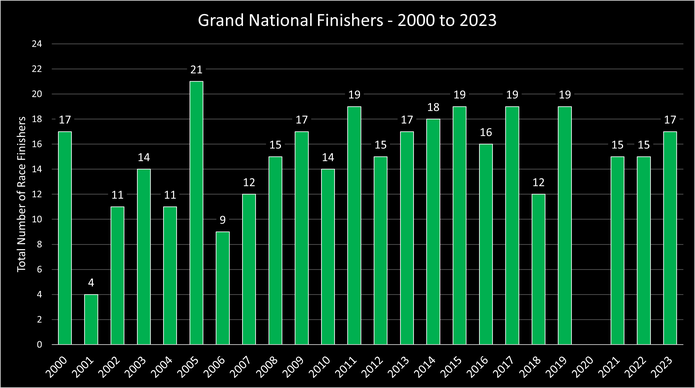

In theory, the number of finishers in the Grand National should be increasing – Aintree course officials and the BHA meet annually to discuss how to make the race safer.

The definition of ‘safety’ should be noticeable in the data of the number of finishers, which should in theory be increasing year on year.

When we look at the numbers, there does appear to be something of an upward trend in the number of horses completing the Aintree circuit – although it’s far from a straight, ascending line.

NOTE: 2020 is missing from the data due to the Grand National being cancelled.

The chart is skewed by a number of anomalies – just four horses finished in the mudbath of 2001, for example, while 21 hit the line in the perfect conditions of 2005.

Clearly, the conditions play a massive part in how many horses finish the Grand National….

How Many Horses Fall in the Grand National?

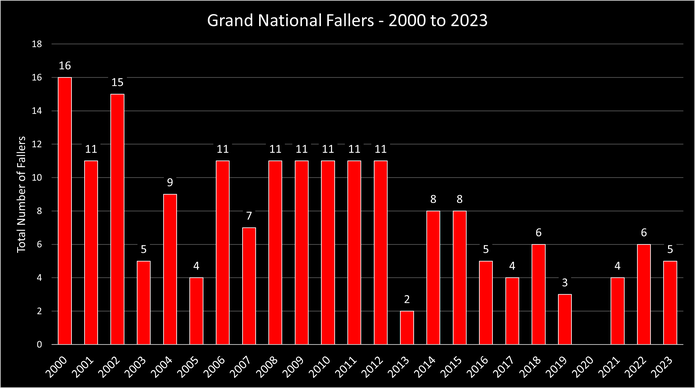

The good news is that, since changes were made to the course and some of the fences, the number of fallers in the Grand National has generally been on the decline.

In the year 2000, 16 horses fell in the Grand National. In 2021, that number had dwindled to four – the line has been trending downwards between those two points.

As you can see, aside from a few anomalies, the number of fallers in the Grand National is trending downwards – that is excellent news for the safety of those involved.

What Affects the Number of Grand National Finishers?

It would be true to say that extremes in weather directly correlates with the number of finishers/fallers in the Grand National.

There are five general types of going: heavy, soft, good-to-soft, good and firm, and when we look at the total number of fallers since 1984 we note that nearly 20% (62) came at the extreme ends of the chart on heavy or firm going despite only six races being run in these conditions.

Heavy ground makes for a very difficult race. It’s slippy upon landing, and at more than four miles a mudbath zaps those in the field of their energy. And yet, happily, bottomless ground is said to cause fewer fatalities, given that it tends to be more forgiving to bones and joints.

At the other end of the spectrum, firm going tends to promote a faster race – not ideal given the length and complexity of the Grand National circuit. These editions tend to lead to more horses being pulled up.

Can a Jockey Remount During the Grand National?

For years, an unseated jockey could remount their horse during the Grand National if they could somehow flag their entry down and climb back on board.

But that was outlawed in November 2009 by the British Horseracing Authority (BHA), who will disqualify any jockey that attempts to remount.

What’s more, jockeys are prohibited from riding their horses back to the paddock or the stables once they have been unseated or fallen – first, the horse has to be checked by veterinary staff, and is led away accordingly.