Football Index Closed: What Happened?

Football Index’s demise was one that truly rocked the gambling industry. Prior to their collapse, they were a huge name with a massive customer base. Such was their stature that they featured as the main shirt sponsor for then-Championship sides Nottingham Forest and Queens Park Rangers. Although very much seen as a legitimate business, with many notable endorsements, the aftermath of their bankruptcy revealed this was far from the case.

Although much blame went to people high-up in the business, the UK Gambling Commission also came under heavy fire. Their failure to fully understand the complexity of what Football Index offered, and their slowness to react, made them just as culpable in the eyes of many people. The Commission is well experienced dealing with traditional bookmakers but Football Index was far from this. Instead, what this doomed-to-fail company offered was a ‘football stock market’ in which users bought and sold shares in players.

A footballing stock market was a truly unique product and for many years the company enjoyed high levels of satisfaction. Back during their prime years, they regularly claimed that only 2% of their players felt they tended to lose money while 74% did so through traditional gambling. It may have lacked huge wins but a steadily increasing portfolio allowed hundreds of thousands of customers to make gradual gains through their footballing knowledge.

Background

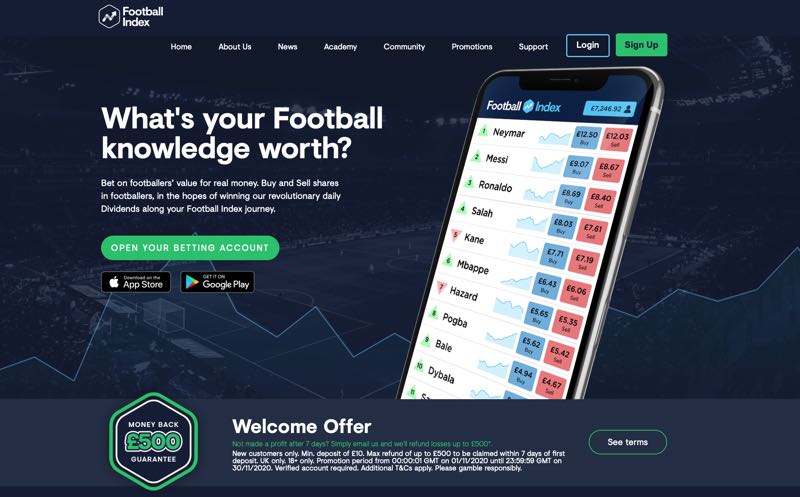

Although Football Index is included as part of our ‘closed bookies’ series, it really wasn’t a bookmaker by any generally understood sense of the word. Rather, it provided a platform in which users could buy and sell shares in real-life players. By owning shares, you could also receive dividends either through the form of match day dividends or media dividends. Basically, if a player performed well or had been making the headlines, you would receive a few pennies per share. While this may not sound like much, player shares could be bought for pennies or pounds so as a percentage return, the dividends were significant.

Over the course of a season, you could enjoy a decent return through these dividends. The shares themselves did expire after three years but players were free to sell them off prior to this point and buy fresh ones. To sell shares, customers could join the queue to sell them to other Football Index customers or sell them back to Football Index through the ‘instant sell’ feature.

In short, this is how the system worked and it proved attractive among punters looking for a change from a typical betting experience. In total, Football Index had around half a million customers with some holding huge, six-figure portfolios. In addition to this, the official Football Index forum had around 35,000 users in which discussions about certain players took place. With so much activity on the platform, at the time of their collapse, it was estimated that active investments totalled as much as £90m.

Global Health Crisis Creates Problems

The global health crisis in the UK put a temporary halt to football across the nation. Worried that people would simply sell their shares as a result, the Football Index hierarchy removed the ‘instant sell’ function from their site. As a result, the only way now to sell players was for another user to buy them. This return to the so-called ‘eBay’ model, while unpopular, was taken to avoid a sudden market crash.

While this limited the number of shares sold, people were buying far fewer shares at this time too and this sparked trouble. Although Football Index later strongly denied any accusations that it was any kind of pyramid or ponzi scheme, the company did rely on new a constant stream of new customers coming in. One document sent to the UK Gambling Commission in January 2020 argued that “should user growth stop or decline, the company would quickly find itself unable to pay these liabilities to users.”

At the same time, the Guardian’s Greg Wood published an article that increased awareness of the possible dangers Football Index customers faced. Despite the efforts to prevent the market crashing, he noted that certain players had seen their value slashed in recent months. Jadon Sancho, for example, was valued at £15.04 in September 2019 but by 22nd December this had dropped to just £5.28.

The article also noted that Caan Berry had raised concerns about Football Index on his YouTube channel but he was met with a potentially “coordinated campaign of abuse and intimidation”. After being flooded with abusive comments, YouTube actually informed Berry that they would be demonetising his account, although this was later retracted. One of Berry’s biggest concerns was that in the terms and conditions of Football Index’s site, it stated that they were free to make changes to the dividend structure even after shares had been purchased.

This concern regarding dividend fragility was far from unjustified fearmongering as just a few months later Berry was fully vindicated. On Friday, 5th March, 2021, Football Index informed traders that their market would be suspended overnight as they made significant changes to how it operated. One of the most controversial changes involved slashing dividend payments. Prior to the change, a customer could earn as much as 33p in dividend payments during a single day but this amount was cut to just 6p. Such a drastic reduction of dividend payments naturally saw the market crash upon reopening.

Chaos Ensues

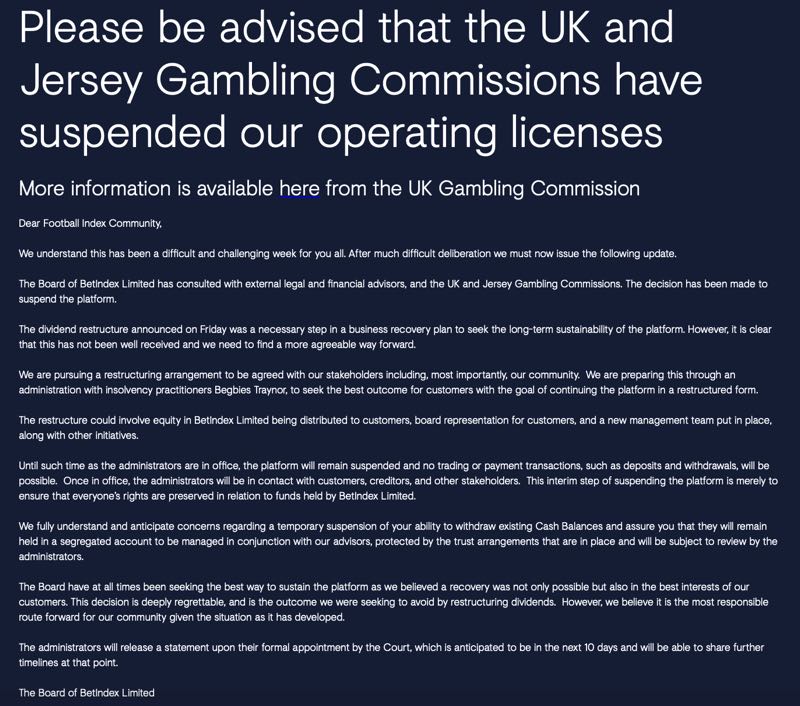

As you can imagine, news of the dividend cuts went down like a lead balloon with Football Index customers but more bad news followed very soon after. On 11th March, the company responsible for Football Index, BetIndex Limited, released a statement announcing that the firm would be going into administration as they looked to continue their platform in a restricted form. The same day the UK Gambling Commissions suspended its operating licence, meaning it could no longer legally trade.

BetIndex also confirmed that until the administrators are in office, no payment transactions would take place. Therefore, all Football Index customers with owned shares or had money in their account had no way of accessing their funds or investments. This, of course, created a great deal of panic as some users had hundreds, if not thousands of pounds tied up in the company.

At the time, Football Index stated in their terms and conditions, that they provided a ‘medium’ level of customer funds protection. This rating, which is awarded by the UK Gambling Commission, meant that customer funds are kept in accounts separate from business accounts. As such, should the company be made insolvent, arrangements should be made to ensure the customers’ assets are returned to them.

Although this did not occur immediately, the High Court of England and Wales ruled that money players had in their accounts up to 26th March should be paid back. In total, this meant returning £3.5m of the £4.5m held in the customer account. The Jersey Courts set 22nd June as the date to recognise this ruling with payments following soon afterwards. An important element to note here is that the ruling only covered money held in player wallets. It did not impact any funds that were tied up in shares (or ‘active bets’ as they were called).

As the funds were being held by the Viscount of Jersey, there was no way of BetIndex delaying or stopping the payment to customers. Still, this was just a tiny fraction of the approximate £90m that was invested within the Football Index platform. For these many players that had virtually all their money in shares rather than in their wallets, they were not so fortunate.

Most Players Lose Out

While some players simply accepted their losses and moved on, there were others who understandably demanded more action. No guarantees were ever made to players with ‘active bets’ as Football Index has such huge liabilities and so little money. Some had asked the UK Gambling Commission to come to the rescue but interim chief executive, Andrew Rhoades, reiterated in September 2021 that the regulator cannot pay back money that has been lost.

In a press released, he simply told customers that the best (and only) avenue of recovery was to get in contact with the administrators. While it is possible that some people could recoup some part of their money this way, it is difficult to get much out of a debt-ridden company.

Who Is to Blame?

It would be incredibly unfair to blame Football Index customers for any of this. Although Rhodes reminded the public that “nobody should bet more than they can afford to lose”, it does not fairly apply in this situation. Shares were seen and regularly advertised as being investments rather than bets. Players acknowledged prices could go up and down and accepted that risk, but not the risk that their entire portfolios could be worthless overnight. After all, Football Index was a fully licensed company that had been in operation since 2015 and one that had many credible sponsorships.

It would be incredibly unfair to blame Football Index customers for any of this. Although Rhodes reminded the public that “nobody should bet more than they can afford to lose”, it does not fairly apply in this situation. Shares were seen and regularly advertised as being investments rather than bets. Players acknowledged prices could go up and down and accepted that risk, but not the risk that their entire portfolios could be worthless overnight. After all, Football Index was a fully licensed company that had been in operation since 2015 and one that had many credible sponsorships.

BetIndex

Instead, the main culprits appear to have been the senior employees of BetIndex. Even from the beginning they did not “properly notify the Gambling Commission of the nature of the product in its licence application” according to an official Government report. Effectively, what they had launched was akin to a Ponzi scheme that relied on new players depositing in order to pay out dividends.

This is what Matt Zarb-Cousin of the Campaign for Fairer Gambling argued while also calling Football Index an “unsustainable business model”. While others disagreed with his damning comments, evidence does suggest that Football Index would have eventually run into trouble. Less generous dividend payments could have avoided the problem but then they might have struggled to attract new customers in the first place.

To make matters worse, days before their impending collapse, Football Index continued to ‘mint’ and issue new shares. By this point, all involved knew how bad the situation was yet they continued to claw back as much money as they could from unsuspecting customers. In February, a month before the collapse, they issued 300,000 new shares across the platform. They also took the bizarre decision, in August 2020, to increase dividend payments despite it already costing them £1m a month.

UKGC

For all BetIndex’s failings, a good portion of the blame must also go to the UK Gambling Commission who failed to grasp exactly what was being offered. Football Index founder, Adam Cole, admitted himself on a podcast that “the Gambling Commission doesn’t fully understand all the ins and outs of our business model”. They were quick to issue a licence despite understanding the full nature of the product. The government’s independent report that looked into the entire fiasco concluded that the UKGC should have scrutinised the product much earlier and questioned some of the language used.

The UKGC were so passive for much of Football Index’s life that by the time their concerns grew, millions upon millions had already been invested. Only in 2020 did the Gambling Commission become fully aware of what was going on but they avoided suspending its licence due to the negative financial impact it would have. The decision to delay taking action was ultimately a mistake as it was merely delaying the inevitable.

A Possible Return?

During the administration process, BetIndex directors initially hoped to relaunch the Football Index brand, as part of a company voluntary arrangement. The plan would see customers who are owed funds, given a 50% equity stake in the new business should such a deal be approved. No doubt many of the people burned by Football Index would not want to be part of its revival but it would potentially allow them to recoup some money.

While it may be possible to have a sustainable football stock market, it is hard to see how Football Index could ever be the one running it. They have lost so much consumer trust that no matter how much they try and rebrand things, consumers will be far too wary. Should any company attempt a similar business model again, it will at least be scrutinised far more highly by the UKGC. Far more stringent regulations are in place now including a strengthened memorandum of understanding between the UKGC and Financial Conduct Authority.