At the time of writing this article, some giant clubs of world football were in the midst of a monumental crisis.

At the time of writing this article, some giant clubs of world football were in the midst of a monumental crisis.

One of the most egregious falls from grace is that of Santos, the second-most successful club in Brazilian football history who brought the world Pele and Neymar, to name just two.

But they will be noticeable by their absence during the 2024 season – they were relegated to Serie B for the first time in their 111-year history in 2023, with financial mismanagement and behind-the-scenes ructions leading to their demise.

That’s a common theme for a number of footballing fallen giants. As the 2023/24 season draws to a close, FC Kaiserslautern – four-time Bundesliga champions, with their most recent title coming in 1998 – are in danger of being relegated to the third tier of German football, having already spent four seasons in Liga 3 between 2018/19 and 2021/22.

It’s not impossible that Schalke, seven-time Bundesliga champions and former UEFA Cup winners, will join them in the 3. Liga, where they may bump into Dynamo Dresden, the most successful team in German football back in the 1970s.

There’s similar scenes in France, where Girondins de Bordeaux – six-time Ligue 1 champions – find themselves just six points clear of the relegation zone in Ligue 2, while in Italy, classic outfits like Sampdoria and Brescia find themselves ensconced in the second tier.

Cautionary tales in English and Spanish football come courtesy of Derby County, Portsmouth and Malaga, who at least seem to have found some kind of solid foundation in 2023/24.

So how do these giants of the main European leagues fall on such hard times, and are there any repeat pitfalls that others need to avoid?

Sorry Santos: Brazil’s Breeding Ground

For context, Santos’ demise – going from Copa Libertadores final in 2020 to relegation in 2023, would be the equivalent of Liverpool reaching the Champions League final and then being relegated from the Premier League three years later.

Unfathomable, you might think. But football’s fallen giants have a knack for achieving the improbable.

Only Palmeiras have won more Brazilian Serie A titles than Santos, and when you see the quality of players that the Alvinegro have either developed or signed over the years, you know why.

Pele is Santos’ most famous son; a player who, if around today, would surely command a transfer fee in excess of £100 million. So romantic was the pull of playing for Santos, the legendary striker stayed for pretty much the entirety of his career – eschewing the chance to move elsewhere. Socrates, another of Brazil’s vintage generation, also pulled on the famous black-and-white shirt at the same time.

And then there’s Neymar. He came through the youth ranks at Santos, making his first-team debut at 17. He stayed for four seasons, helping the club to the Copa Libertadores title – the American continental equivalent of the Champions League – before departing in 2013 to join Barcelona, for a fee in the region of £75 million.

Because there’s not a huge amount of money sloshing around in Brazilian football, their brightest talents tend to get picked off on the cheap by clubs from Europe and elsewhere – but Santos, all told, have done pretty well from selling their key players over the years.

- Neymar (Barcelona, £75 million)

- Rodrygo (Real Madrid, £38 million)

- Gabriel Barbosa (Inter Milan, £25 million)

- Robinho (Real Madrid, £20.5 million)

- Marcos Leonardo (Benfica, £15.5 million)

With the exception of the Robinho deal, all of these sales have occurred within the past decade – ensuring Santos are one of the most financially liquid clubs in Brazil.

So how on earth do they find themselves in Serie B?

As ever, it’s mismanagement off the pitch that has been the main contributory factor. Despite those player sales, Santos have racked up debts in the region of £110 million – forcing players to be sold, which in turn has led to a consistent degrading of the quality of their squad year on year.

Andres Rueda, the club’s former president, also developed a reputation for being trigger-happy in the hiring and firing of his head coaches – since the start of 2022, Santos have had five permanent managers at the helm.

That lack of continuity, and the financial burden that has led to forced player sales, sent Santos on a downward spiral – culminating in a heartbreaking relegation, confirmed by a last-minute goal conceded against Fortaleza, which sparked riots both inside and out of the Vila Belmiro stadium. To make matters worse, this was the first full Serie A season since the death of Pele, which was met with a period of national mourning.

Santos’ youth academy is famous for producing the stars of tomorrow, and the club will be forced to lean on them even more as relegation forces an even tighter grip of the purse strings. Depending on their development, it could be years before the famous black-and-whites are challenging for Serie A honours once again.

Decades of Decline

Some clubs, think Derby County and Portsmouth, face a short, sharp plummet down the leagues – making it difficult for their supporters to even comprehend what has happened.

But for others, the decline is gradual – and the impact of that catastrophic.

FC Nurnberg

German football has more than its fair share of fallen giants. Modern day fans recognise Bayern Munich, Borussia Dortmund and Bayer Leverkusen as the dominant forces, but that has not been the case historically.

Indeed, a handful of the most successful clubs in German football history don’t even compete in the Bundesliga anymore. Only one side has won more top-flight titles than FC Nurnberg, who dominated in the pre-war era and picked up three more championships thereafter too.

Today, they’re little more than a mid-table concern in the second tier of German football – more likely to suffer relegation than promotion back to the top-flight.

Whereas Nurnberg’s decline has been slow and steady, the same cannot be said for three of Germany’s other most decorated teams: Hamburg, Schalke and Kaiserslautern.

Hamburg

Hamburg held a remarkable record: they were the only club to play continuously in the German Bundesliga since the First World War, winning six titles and the European Cup in 1983. Readers of a certain vintage will remember a certain Kevin Keegan causing shockwaves by moving to Hamburg in 1977, leaving the then European champions Liverpool to do so.

By 2006, Hamburg were still qualifying for the Champions League – but the rot had began to set in. It finally happened in 2018: relegation to the second-tier for the first time in the club’s history.

They’ve stayed there ever since, experiencing heartache in their bid to return to the Bundesliga – on the last day of the 2022/23 season, closest rivals Heidenheim scored twice in injury time to secure promotion ahead of Hamburg in crazy fashion.

Kaiserslautern

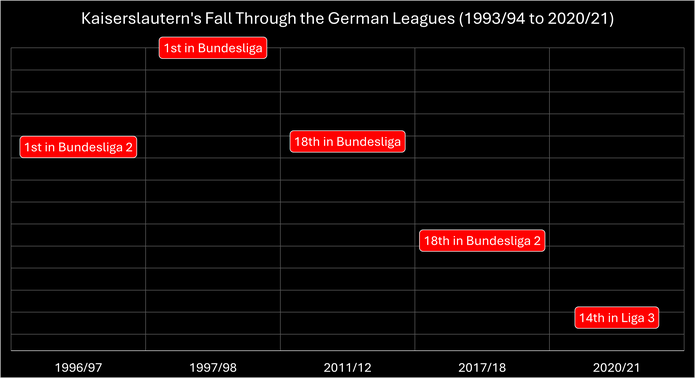

The fall from grace of Kaiserslautern, meanwhile, is even more extraordinary:

In 1997/98, they won the Bundesliga title – cementing their position as the best side in German football.

But, by 2002/03 they were down to 14th in the Bundesliga, and by 2007/08 they were effectively only the 31st best team in Germany, finishing 13th in Bundesliga 2.

Worse was to come. In 2017/18, they finished bottom of the second-tier, spending three seasons in 3. Liga – in 2020/21, they would finish a lowly 14th there, capping a catastrophic slide from champions to also-rans in little over two decades.

Kaiserslautern have rallied, somewhat, since, with promotion back to the second tier, although they are facing an almighty relegation battle in 2023/24 once more.

The source of their woes? You guessed it: financial mismanagement. All sorts of shenanigans in the late 1990s saw the club’s directors hauled in for questioning over allegations of tax evasion, and a sizable fine added to debts in excess of £50 million. By 2003, they were forced to sell their stadium.

When a former CEO took over at the club in 2016, he remarked, ‘there is no money there’ after examining Kaiserslautern’s accounts. As we know in football, a lack of cashflow generally precipitates a downward trend.

A French Farce

You may know Bordeaux as a region that produces some of the best wines to be found anywhere on the planet.

That in itself has put the city on the map, but their football team has also been a considerable presence in progressing the Bordeaux name – or at least they were, anyway.

Girondins de Bordeaux, to give their full name, have won the Ligue 1 title on six occasions – most recently in 2009 – and the French domestic cup four times, including as recently as 2013.

They are, historically, a relative powerhouse of French football, but they have fallen on hard times and, heading into the business end of the 2023/24 season, they find themselves in a position of potential or fear, depending on whether you are a glass half-full or empty merchant: Bordeaux are six points off the play-off places in Ligue 2, but also six points off the relegation places too.

Theirs is a tale of extraordinary self-destruction – from unearthing a young Zinedine Zidane to almost annihilation, all in the space of three decades.

Zinedine Zidane in action for Bordeaux against AC Milan. pic.twitter.com/xWqdxn6NN0

— 90s Football (@90sfootball) December 18, 2023

It all started in 2018, when the club’s former owners – French media firm M6 – sold a controlling stake to General American Capital Partners. Within three years, they claimed they no longer had the financial means to support the club, so they sold it (at a reduced rate) to Spanish entrepreneur Gerard Lopez.

Bordeaux needed to make money, and fast, so they sold more than £50 million worth of talent in 2019/20 – reinvesting just £14 million of that back into replacements. In 2020/21, they sold players to the tune of £15 million, but didn’t spend a single penny on reinforcements; instead relying on reserve players and a single loan signing.

They sold £16 million of players in 2021/22, spent less than half on replacements, and three years of talent drain and downgrading ultimately led to them finishing bottom of the Ligue 1 table.

Fast forward and now Lopez wants to sell up too, although there’s not exactly a long queue of suitors waiting to acquire a football club riddled with debt, playing in a council-owned stadium and whose player selling spree has left them struggling to compete in Ligue 2, let alone the top tier.

If Bordeaux need any inspiration for a revival, they should look no further than Saint-Etienne, a club so steeped in history that only PSG have won more Ligue 1 titles than them.

They were relegated to Ligue 2 at the end of the 2021/22 season, where a riotous play-off defeat to Auxerre saw a year of frustration boil over into unsavoury scenes on the pitch – so unsavoury, in fact, they were docked three points for the 2022/23 campaign and forced to play four games behind closed doors.

Saint-Etienne were in the relegation zone halfway through 2022/23, but steadied the ship, rallied to mid-table safety and carried that momentum into 2023/24, where they are very much in the promotion picture heading into the final weeks of the campaign.

Italian Stallions Lose Their Power

In the early 1990s, Sampdoria won the Serie A title and reached the European Cup final – only Barcelona were able to stop their rise to the top of the beautiful game on the continent.

This was a team of stars of today and tomorrow: Gianluca Vialli, Roberto Mancini, Gianluca Pagliuca and Attilio Lombardo just four of those to pull on the famous blue shirt.

Sampdoria remained a force for the next decade, spotting talents like Juan Sebastian Veron, Ariel Ortega and Clarence Seedorf and moulding a team that continued to finish in the upper echelons of Serie A.

But mismanagement off the pitch, and a decline on it, saw Sampdoria become something of a yo-yo club, suffering a series of relegations. By 2014, the club had been acquired by Massimo Ferrero, a film producer with a, shall we say, colourful past – he made no secret of the fact that he supported Samp’s Serie A rivals Roma too, which did little to ingratiate him to the fans.

Ferrero was arrested in 2021 as part of an investigation into corporate criminality, and while he stepped down as Sampdoria president, he remained as the majority shareholder. After refusing to sell up, a pig’s head and a letter containing bullets were addressed to Ferrero amid growing supporter unrest.

Eventually, former Leeds United owner Andrea Radrizzani was able to persuade Ferrero to sell his majority share, and he instantly appointed Andrea Pirlo as head coach – a move designed to appease the club’s increasingly frustrated fanbase.

Pirlo has overseen some progress on the pitch, at least, and heading towards the end of the 2023/24 season Sampdoria are in the mix for one of the play-off places in Serie B.

Ideas Above Their Station

Perhaps the most cautionary of cautionary tales comes courtesy of Malaga CF.

Although they couldn’t be described as a giant of football in the truest sense, they did reach the Champions League quarter-final in 2013 – just a few years after plying their trade in the third tier of Spanish football.

One man, with deep pockets and big dreams, was considered responsible. Cash rich Qatari entrepreneur Sheikh Abdullah Al-Thani had swept through Malaga like a hurricane, acquiring the club in 2010 and immediately setting about improving their fortunes.

Manuel Pellegrini was appointed head coach, the likes of Ruud van Nistelrooy, Santi Cazorla and Isco were signed, and soon Malaga were snapping at the heels of the Spanish football elite.

Unfortunately, it wouldn’t be long before Al-Thani’s dream became a nightmare.

There were rumours that he had run out of money, with work on a rejuvenation of Marbella’s marina – which the Qatari had promised to part-fund – coming to a grinding halt.

Whispers about the owner’s situation were reflected in a lack of investment in the football club, and mounting debts went unpaid – Al-Thani, who had all but disappeared at this point, had no way of paying them off.

Malaga were relegated to La Liga in 2018, and in an unusual step Al-Thani was legally removed as club president by the Spanish courts over alleged ‘misappropriation’ of funds.

Since then, Malaga CF have been stabilised financially but suffered ordeal after ordeal on the pitch – their lack of resources, and working through nearly a dozen managers in three years, has seen them slump back to the third-tier of Spanish football….where Al-Thani found them all those years ago.

So, if you support a footballing giant in Europe or South America, the message is simple: be careful what you wish for. You might just get it….