The 2024 Olympic Games are noteworthy as they come exactly one century since Paris last hosted the extravaganza.

The 2024 Olympic Games are noteworthy as they come exactly one century since Paris last hosted the extravaganza.

Why has it taken so long for the Games to return to the French capital? There’s sporting and political reasons, although it would be true to say that 100 years is far too long for the Games to evade Paris.

Maybe the reason they have finally returned is that sports governors in France have forgotten the turmoil that the 1924 Games cost the country – hosting the Olympics yielded a net loss of 5.5 million francs….adjusted for inflation a century later, that would be a cool 271 million francs!

No wonder authorities in France were so reluctant to host the Games again, but this is a new generation who believes that the country – and specifically Paris – should be put on the Olympic map once more….despite costs estimated in the region of £3.1 billion, which is a surprise given how much sporting infrastructure is already in place in Paris.

A large proportion of that will come from private funding, although the State will have to fork out around £1.1 billion – much of which will come from the taxpayer.

The good news is that at least the Olympic Games makes money for its host city….right? Well, no, actually. Although the Winter Olympics have been something of a cash cow over the years, the Summer Olympics have been anything but.

What are the Costs of Hosting the Olympics?

Pulling off hosting duties for the Olympic Games is a mammoth task – and one that requires significant investment for even the most advanced and economically viable cities.

They need a ‘headquarters’ style stadium, one which can host the opening and closing ceremonies in front of huge crowds, as well as welcoming the myriad track and field events – including suitable size and scale to host the throwing disciplines like the javelin and discus, which need plenty of room so that spectators aren’t in any peril.

But that’s only a drop in the ocean of the sporting infrastructure needed. Think about all of the other sports that are contested: football, boxing, basketball, cycling, skateboarding, sailing, tennis and the indoor aquatic events, to name just a few. These all need a safe and sufficient home, while the road marathon needs to have a viable route that navigates its way around the city.

These all cost money – and there’s often concerns about the legacy of new builds constructed to host the Olympics; that said, in London in 2022, some 95% of the permanent venues built to host the 2012 Games were still operational.

Added Infrastructure

Aside from the sporting costs, the host city also needs to splash out on the necessary infrastructure of hosting 15,000 or more athletes, coaches, support staff and officials in ‘Olympic villages’, while transport networks need to be of a sufficient quality to cope with the demands placed upon them by sports fans wanting to travel around the city.

As anyone that has travelled by train to work on a regular basis can attest, the railway systems in many Olympic cities struggle to cope with the daily commute, let alone an event of the scale of the Games – this all requires significant investment.

To offer some more context, the London Games required 40,000 hotel rooms or accommodations to be made available for travelling spectators. If there’s not enough hotels to facilitate that, then guess what? More will be built on any available parcel of land.

What’s interesting about the Winter Olympics is that only a select few cities can host the Games – they need the low temperatures and the outdoor facilities, first of all, as well as the landscapes necessary for disciplines like alpine skiing. But for the Summer Olympics? There are very few barriers to entry, as long as the funding is in place to turn a city into a location able to host a major sporting event.

Those are the costs of hosting the Olympics and ensuring all involved can travel safely and reliable, but there’s a stack of other ‘operating costs’ to factor in too, including event management, security, marketing and paying for the opening and closing ceremonies, with their considerable planning and execution in music, lights and fireworks.

The bill routinely runs into the billions, and yet it’s not easy to monetise the Olympics and get some or all of your investment back in profit.

So the simple question remains: why bother hosting the Olympics at all?

Has Any City Made Money from the Olympics?

The Olympic Games was first contested in its ‘modern’ era way back in 1896, when Athens took on hosting duties.

The Summer Games operated on a far smaller scale back then, with just 14 nations sending a squad of just male athletes – around 240, in total – to compete in just nine sports (and ten disciplines overall).

Even in that’s tripped back fashion, the 1986 Olympics cost Athens around 3.7 million drachma to host. They made about 1 million of that back in ticket sales, the selling of a set of commemorative stamps and charitable donations, with the people of Greece alone contributing approximately 330,000 drachma.

But the ultimate saviour was George Averoff, a Greek entrepreneur and philanthropist who personally donated 1 million drachma to ensure the Games went ahead at the restored Panathenian Stadium.

While a legacy of sporting excellence was put in place that would last for more than a century – and counting, the 1896 Olympics also laid the foundation for how difficult it is to make a profit from hosting the Games.

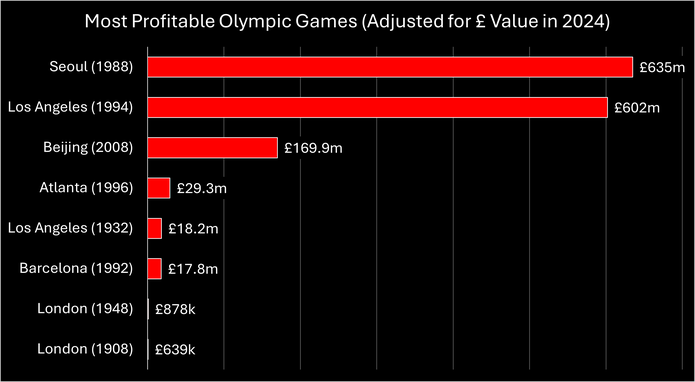

Although data isn’t available for all editions of the Summer Olympics, we know that just eight hostings of the extravaganza have made their host city a profit.

There’s been some liberties taken here, with some of the profit figures reported by Olympics officials particularly neat and rounded figures – suggesting that they’re estimations, rather than exact numbers.

But even so, you can see that some editions of the Games have seen some very handsome economic gains for their hosts. With the given figures adjusted for 2024 inflation, we can see that London put on two profitable editions of the Olympics in 1908 and 1948 – albeit not running into the millions enjoyed by others.

Los Angeles are the undoubted masters of hosting the Olympic Games – no wonder they were so keen to be selected as the hosts in 2028.

The 1932 Games were extraordinary. Held during the Great Depression, Los Angeles was able to turn a profit despite being the first host to commit to building an exclusive Olympic Village for its participants – paying for their food and hospitality for the duration of the Games.

The key was that the event was not financed by the government or the state, but utilised private investment and strategic partnerships to pay for the improvements in sporting venues and infrastructure.

Happily for organisers, L.A. already had a strong transport network and a number of facilities in place already, which also contributed to the lowering of their costs – officials reported a profit of around $1 million, which adjusted for inflation and exchanged for BGP works out at £18.2 million today.

Fast forward to 1984, with Los Angeles again voted to host the Olympics. With the necessary sporting and transportation infrastructure in place already, officials could simply focus on making money – which they did, to the tune of $250 million (£602 million when adjusted for inflation and exchanged to Pound Sterling).

This was the first Games to make a profit in the contemporary era, and one of the first to be run with the financial efficiency of a business – many of the facilities used in 1932 were simply given a facelift, as opposed to new stadia being built from scratch. Corporate funding, as opposed to state expenditure, also helped to protect L.A’s bottom line.

It’s an operating model adopted by the next three host cities of the Games – Seoul, Barcelona and Atlanta – who would all yield a profit from hosting the Olympics.

The numbers from Seoul ’88 are truly extraordinary. The official profit from the event was recorded as $300 million, which when adjusted for inflation and exchanged into GBP confirms this to be the most profitable Olympic Games in history.

The figures can be argued – this was a government-funded edition of the Olympics, and so ‘profits’ are recorded with view to the overall economic gains experienced, as opposed to an Olympic-only profit and loss account. On that note, the South Korean treasury noted a 12% growth in their economy thanks to the fortnight of hosting the Games alone.

Beijing also made a healthy profit in 2008, which came in part due to the huge corporate and commercial sector sponsorships generated. Running a ‘privatised’ Olympic Games, while perhaps not in the community spirit, does at least ensure money is made – not always the case, it has to be said.

Which Cities Have Lost the Most Money from Hosting the Olympics?

It does make you wonder what goes through the heads of Olympic committees in individual countries where billions would have to be spent on simply hosting the games – why even throw your hat in the ring in the first place?

The reasons for that will be detailed below, but for now we have some monumental financial losses to report – indeed, in some cases, hosting the Olympic Games actually contributed to an economic crash in the host country.

Many moons ago, few host cities had the infrastructure in place to welcome an Olympic Games – hence why editions like Paris 1924 and Helsinki 1952 lost money.

In the more contemporary era, some host cities have well and truly bungled their financial planning ahead of the Olympics:

Montreal were first into the rogues gallery of dreadful Olympic hosts in 1976. So inept was their financial modelling that they ended up spending four times more than what they had forecast – development of the Big O stadium, which has since been dubbed the ‘Big Owe’, ultimately cost the taxpayer a lofty £1.3 billion.

Indeed, so crippled was the economy by the Games, politicians introduced a special tobacco tax, which saw a sixth of a cent from every sale of cigarette packets go towards paying the Olympic debt.

There’s something of an asterisk against the Moscow Games in 1980. When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, 66 nations – including the United States, Canada, China, Japan and West Germany – boycotted the Olympics, which in turn reduced tourism revenue and media rights sales.

Having already committed to hosting the Games, the Soviet economy was left to foot the bill.

If you want to know how not to host an Olympic Games, you can use Sydney’s business model in 2000 as a guide. They overran cost projections by a mammoth 90%, while the construction of Sydney Olympic Park – which was to host much of the action – cost more than £350 million and now plays host to a number of redundant sporting facilities.

Worse still, this was a government-funded Olympic Games, and they did what all governments do in this situation – they passed on the cost of hosting the Olympics to the taxpayer, many of whom did not even want to host the action in Sydney in the first place.

Greek Tragedy

At least the Australian economy was able to rally from such a monumental loss. But in Athens in 2004? Not so much….

This was supposed to be a celebratory edition of the Olympics, with the Games returning to their spiritual home all those years later. Athens benefitted from a new airport, roads and metro system to help facilitate the showpiece occasion.

But all of that came at a cost. Although unconfirmed, some fiscal experts have claimed that hosting the 2004 Olympics helped to facilitate the sovereign debt crisis that engulfed Greece for much of the 2010s.

In the end, the Greek government forked out a total of £7 billion to host the games, which yielded a net loss in excess of £19 million. And they were accused of overspending too in the wake of warnings from the International Olympic Committee (IOC), who threatened to move the 2004 Games to a new host city as officials in Athens struggled to make infrastructure improvements.

And, sadly, Athens has now been left with a host of ‘white elephants’ – that is, sporting facilities constructed for the Olympics that now sit abandoned and unused.

Did Rio de Janeiro learn the lessons of history in 2016? Did they heck!

The Brazilian city was more than £2 billion in the hole by the time it had completed its preparations for hosting the Olympics – for a location with high count of extreme poverty, that really was worrying to say the least.

Organisers spent more than $13 billion on getting Rio into shape, but would only recoup $11 billion in revenue – marking out the 2016 Games as one of the most expensive mistakes in Olympic history.

Although Rio had plenty of elite football stadia already, they weren’t as well stocked as far as multi-purpose venues were concerned – hence why nine new facilities were built just for the Olympics. To continue their extravagant spending, officials also forked out for the largest Olympic Village ever seen.

All of the above, plus extras including 5km worth of urban regeneration projects and 200km of security fencing, made it almost impossible for the Rio Games to be financially viable.

Do Cities Benefit from Hosting the Olympics?

So if the financial costs are known to be so stratospheric, why bother hosting the Olympic Games in the first place?

The answer is a series of tangible and intangible benefits. The idea is that hosting the Olympics boosts tourism thereafter, with the city and its local environs marketed in a way to make them appear vibrant and exciting – even if that’s not exactly true.

But some host cities did not experience an economic gain post-Games, with cities like Athens and Rio seeing only a negligible rise in visitors. Incredibly, three cities – London, Beijing and Salt Lake – all reported a downturn in tourism in the year of hosting the Olympics.

Other arguments include improved infrastructure (why not improve your transport network without hosting the Olympics?), the creation of new jobs (most of which are temporary contracts) and economic gains, of which the evidence is mixed to say the least.

Some host cities will use the Olympics in a bid to increase the local participation rates in sport – an easy PR win. But again, the data does not necessarily indicate that the shiny new squash courts and cycling velodromes are used after the Games are over; in London, following 2012, studies revealed that sporting participation had actually decreased in the aftermath of the summer showpiece.

It is possible to host a financially viable and even profitable edition of the Olympic Games, but only in cities with a strong infrastructure and sporting landscape in place already.

Without that, and without cash-rich backers to pay for city-wide improvements, the Olympics are like to become another battleground for ‘soft power’ in the way that football’s World Cup has.

Expect a future edition of the Olympic Games in the Middle East very soon….