Of all the major sports played around the world, cricket is perhaps the only one still ruled by traditionalists and puritans – those with a sense that the old way is still the best way.

Of all the major sports played around the world, cricket is perhaps the only one still ruled by traditionalists and puritans – those with a sense that the old way is still the best way.

That explains why the members of the MCC rejected the idea of twenty-twenty cricket in 1998 – that simply did not sit right with those for whom the sport was about lazy summer days in the sun, the sound of leather on willow a comforting lullaby as they drift peacefully into their afternoon naps following a lunch of prawn sandwiches and a glass or two of fizz.

Fast forward 25 years and T20 cricket, as it is now known, is the pre-eminent format of the sport, the most-watched form of cricket around the world, in which scores of 200+ runs are regularly recorded.

For the dusty godfathers of quintessential English village greens, it still rankles that cricket has moved on and left them behind.

No more evident was that notion than the December 2023 series between England and the West Indies. Jos Buttler’s men, batting first, posted a total of 171 – not huge, by any means, but a score that two decades ago would have been enough to win the vast majority of T20 games.

However, these are different days now, and the West Indies would no doubt have been licking their lips of such a gettable target in Barbados – so it proved, with Andre Russell blasting the winning runs with some 11 balls to spare. It’s likely that his side would have crossed the rubicon of 200+ had they batted on.

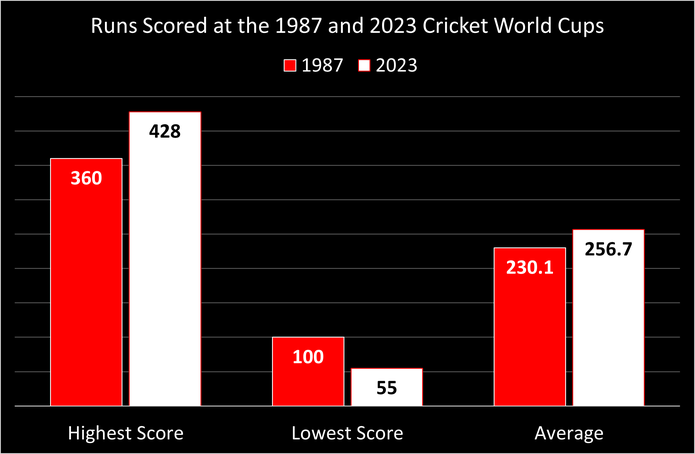

At the 1987 Cricket World Cup, no game saw a score of 300+ posted. At the 2023 edition, that milestone was passed on no less than 25 different occasions.

Cricket has changed and continues to change….which makes you wonder what the future of the T20 format holds.

When Did T20 Cricket Start?

In an alternate reality, there may well have been T20 cricket matches played as early as 1998 – many of the game’s most progressive thinkers wanted a quicker, more urgent format of the sport in a bid to attract a new, younger audience.

The MCC, and many of the English cricket counties it has to be said, rejected the idea – they were happy spending long days in the field despite the rapidly-dwindling attendances.

By 2003, it was painfully obvious that cricket needed a shake-up – the test format remained beloved by purists, but even the sport’s most obsessed ‘badgers’ realised that the 50-over format was achieving very little other than stodgy, unnecessarily lengthy games that nobody wanted to see.

Martin Crowe, the former New Zealand captain, had been working on a shorter format of cricket – known as Cricket Max – which was designed to solve many of the shortcomings of the 50-over game.

Nobody really wanted to entertain the notion, however, but Stuart Robinson, the then marketing manager of the English Cricket Board, decided there was some savvy to the idea.

The idea of 20-over cricket was put forward to a vote – the yays outweighing the neighs by 11-7. The seven seemingly finding the format too radical….just wait until they hear about The Hundred and T10 cricket that would follow.

So twenty-twenty, or T20 as it would later be known for branding purposes, was born in 2003 with the advent of the Twenty20 Cup in England, the first professional competition to utilise the concept.

How Has T20 Cricket Changed?

It would be unfair to be too harsh on those inaugural guinea pigs back in 2003; the 20-over format was completely new to them, so notions of par scores and what was possible were mere pies in the sky in those early fumblings.

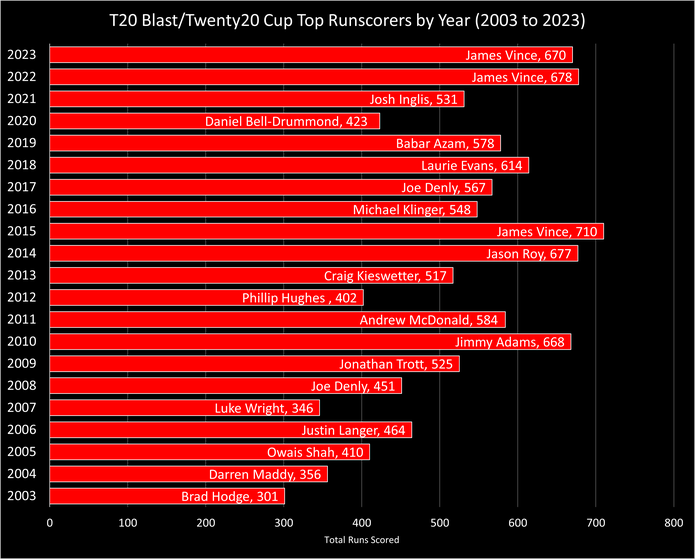

But it is interesting to note the differences in batting styles in particular. Brad Hodge was the leading run-scorer in the 2003 Twenty20 Cup, accumulating his 301 runs at a strike rate of 138.07. By 2023, James Vince was starring in the same competition (now branded as the T20 Blast) with a strike rate of 154.02. Will Smeed, meanwhile, was blitzing 501 runs at a strike rate of 175.50.

For the uninitiated, a batter’s strike rate in cricket is essentially a measure of how quickly they score their runs – it reveals how many runs a batter would score per 100 balls (which is calculated pro rate if they face fewer or more than 100).

And it is this metric that perhaps best describes the key change that has shaped T20 cricket over the past 20 years: not only the weight of runs, but also how quickly they are scored.

You only need to look at the record books to see how T20 cricket has changed, from a batting perspective, in the past two decades. Here’s the highest totals posted by the batting team since 2003 – just look at the dates of when they were made:

Record T20 Batting Totals

| Date | Runs | Team | Opponent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sept 2023 | 314 | Nepal | Mongolia |

| Feb 2019 | 278 | Afghanistan | Ireland |

| Aug 2019 | 278 | Czech Republic | Turkey |

| Jan 2022 | 273 | Melbourne Stars | Hobart Hurricanes |

| Oct 2022 | 271 | The Titans | The Knights |

The five highest-ever scores recorded in T20 cricket have come since 2019 – 16 years after the format was first played. Of the five, three have come since the start of 2022, so evidently the biggest change in T20 cricket has been the ambition in amassing huge totals; aided by strong, gym-going batters wielding heavier, technologically superior bats.

How Have Cricket Bats Changed?

Once upon a time, a cricket bat was a pretty generic item – a piece of willow, lovingly hand-plained and oiled, weighing in the region of 2lbs 8oz.

But as the demands of cricket have changed, particularly in the area of scoring runs quickly, so too has the shape, size and specifications of the batter’s weapon – this is the era of the big bat.

In days of yore, hitting sixes was not a major concern – that was due to the mindset of players, when scoring at a strike rate of 100 was perceived as being plenty, but also due to the willow in their hands; bats were designed for stroke players in the 1980s and nineties, for the most part, and not for those whose main intent is to clear the ropes.

Today, however, many lines of bats are designed specifically for that purpose: lighter pick-ups, chunkier profiles and larger sweet-spots just some of the specifications desired by T20 specialists.

The sweet-spot is the central part of the face of the bat where players would ideally like to hit the ball from. The grains are so tightly-packed here that the ball tends to spring away from the blade, unlike the toe and edged where the wood tends to have a ‘deadened’ effect. Manufacturers have been able to make the sweet-spot bigger over the years, while even chunky edges can carry easily for four runs – increasing the batter’s armoury.

Reverse Sweeps, Ramps and Switch Hits

In 1930, Donald Bradman broke all sorts of batting records – his innings of 334 against England the best ever witnessed at the time.

Cricket statisticians use a graphic known as a ‘wagon wheel’ to show where a batter has scored their runs – be it square of the wicket on the off side or leg side, down the ground or, in a favourite area for village cricketers, the so-called ‘cow corner’ of hoiking the ball down to mid-wicket.

Here’s the wagon wheel of @AlexHales1’s innings so far. 51 from 33 balls #EngvSL pic.twitter.com/DZnQBUWIDm

— England and Wales Cricket Board (@ECB_cricket) May 20, 2014

As you would imagine, Bradman’s wagon when was befitting of an old school purist – most of his 334 was accumulated square of the wicket on both the off and leg side.

What T20 cricket has done is create a need for a more 360° wagon wheel. Not all balls can be hit to the boundary in traditional fashion, so in this fast-paced version of the sport batters have had to find ways to manipulate the ball to all corners of the ground – preventing the opposite bowlers from settling in to a rhythm, while posing the opposing captain a conundrum in how to set his or her field.

To do so, all manner of new cricket shots have been invented over the past decade or so – from reverse sweeps and ramp shots to paddles, helicopters and even switch hits.

Batters have been using the sweep shot for years – a way to caress the ball behind them down to the fine leg fielder or, ideally, the boundary. The reverse sweep requires the batter to turn the bat around in their hands as the ball is in flight, quickly dabbing it down to the third man boundary instead.

A ramp shot uses the bowler’s pace against them, pushing the ball over the wicketkeeper’s head before it races to the rope.

The helicopter, made famous by Indian legend M.S. Dhoni, offers batters a way of hitting sixes on the off side – historically, it has not been easy to get the elevation required to clear the rope in this way.

There’s many other ways that batters are innovating, but all have the same end goal: to manipulate the ball to parts of the ground where there are no fielders present. We all love to see big hitting and sixes hit out of the ground, but runs are runs in modern cricket – it doesn’t matter how they are accumulated as long as they are….and fast.

Come for the ramp shot 😍

Stay for the reaction 😅#EnglandCricket | #Ashes pic.twitter.com/xLoo7VTytM

— England Cricket (@englandcricket) June 17, 2023

How Has Bowling Changed in T20 Cricket?

Really, T20 cricket is a batter’s game – they have the skillset and the training, now that the format is so widely played, to hit the ball where they want; with little that the bowler can do about it.

Bowling in cricket didn’t really change during the 20th Century. Most English youngster are taught to bowl line and length – essentially landing the ball in an area on the pitch that would test the batter’s technique around the top of off stump or just outside (the so-called ‘corridor of uncertainty’).

In Australia and the Caribbean, the sun-baked pitches allow bowlers to pull their length back and even throw in some bouncers for good measure – as the West Indies teams of the 1970s-1990s did with devastating effect.

What T20 cricket has done is shift the paradigm for bowlers, who no longer have the luxury of settling into a rhythm and bowling the same ball time after time – especially in an age where batters have three or four ways to despatch any delivery to the fence.

A T20 bowler, like a baseball pitcher, will now have an impressive array of deliveries at their disposal. Bouncers and slow bouncers are joined by wide yorkers, slower balls and those dug halfway down the pitch in a bid to befuddle a batter and prevent them from hitting the ball where they want to.

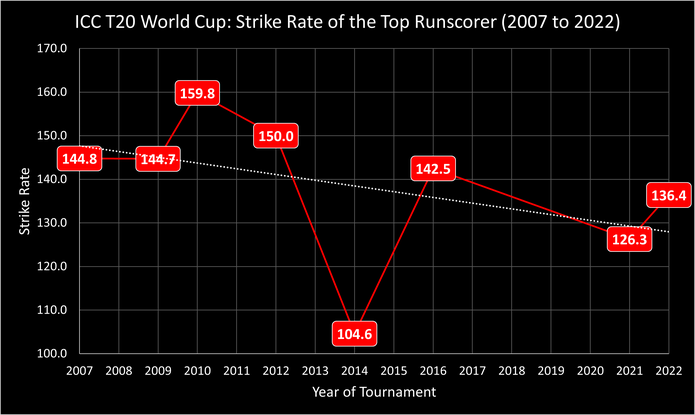

As we’ve already learned, T20 scores are generally getting higher and runs are being accumulated faster, but that’s not to say that bowlers aren’t fighting back with their own brand of ingenuity. The graphic below shows the batting strike rate of the individual that has finished top run-scorer at the past eight editions of the ICC T20 Men’s World Cup:

As you can see from the image and the trend line, the strike rate of batters at the T20 World Cup has actually been in decline – from 144.8 in 2007 to a high of 159.8 in 2010, before falling to 136.4 in 2022.

What’s the reason for this? Conditions play a part – some of these World Cups have been played on spectacularly slow pitches in the sub-continent, but there’s definitely a case to be made that says the innovations of bowlers have gone a long way to usurping the overwhelming dominance of batters in this format.

What Next for T20 Cricket?

Those that have been at the forefront of T20 cricket for a number of years have effectively been learning on the job – many play this short format in addition to four or five day games and 50-over outings.

Those that have been at the forefront of T20 cricket for a number of years have effectively been learning on the job – many play this short format in addition to four or five day games and 50-over outings.

But the next generation coming through….well, many of them will be T20 specialists – they won’t care a dime for playing the longer formats. There’s serious money to be made as a T20 gun for hire, as well as a year-round schedule that takes in England’s T20 Blast, Australia’s Big Bash League, the Caribbean CPL T20 and the Indian Premier League.

Indeed, some will earn more money from franchise T20 cricket than they will for representing their country – a truly sorry state of affairs.

The longer formats of cricket face an existential threat from T20 – in ten years’ time, it’s unlikely that you will see a 50-over game being played anywhere. Ironically, T20 itself faces its own reckoning from even shorter formats.

The ECB has thrown a lot of resources behind The Hundred, a format that effectively shaves 40 balls off the average T20 game and greatly reduces the amount of time that matches take to finish. If they can woo private equity investors as well, The Hundred may send the T20 Blast into extinction.

And then there’s T10 competitions which, you guessed it, are half the length of T20 outings.

One of the perks of T20 cricket back in 2003 – the shortness of the games to suit a society with an ever-decreasing collective attention span – is now its weakness, with The Hundred and T10 formats growing in popularity. Where will it stand in another 20 years from now?