![]() The so-called biological clock dictates that most women are at their most fertile in their twenties and early thirties, which can lead to some awkward conversations no doubt for female athletes at the peak of their powers in that age range.

The so-called biological clock dictates that most women are at their most fertile in their twenties and early thirties, which can lead to some awkward conversations no doubt for female athletes at the peak of their powers in that age range.

They must decide whether to put off having children until the end of their sporting careers – and the potential health risks that come with it, or pause their career and have some time away while they give birth and nurture their new born.

It’s an almighty conundrum, and one that – until recent years – was not helped by some old-fashioned views on maternity leave for athletes. Thankfully, those attitudes have started to change.

But maternity pay for pregnant sports stars? That’s another matter altogether, and one that continues to shape the decisions of female athletes and their loved ones – in some cases, forcing some to not start a family, which in this allegedly more progressive age really is rather nonsensical.

Do Female Athletes Get Maternity Leave?

Before we even get onto the topic of maternity pay, it’s amazing to learn that female athletes didn’t even get statutory maternity leave until recently – in fact, some sports didn’t even introduce such a policy until 2023.

There were legal ramifications of that – why wouldn’t a sports team be held to the same standards as any other workplace? As such, clubs that employ players as salaried ‘workers’ have been brought to account, with the vast majority of sports now governed by legislation on the matter.

But as for individual sports….well, that’s where things become a little more challenging. A track athlete or a tennis player are, in essence, self-employed – in the UK, self-employed workers are entitled to a ‘maternity allowance’ payment in addition to the length of leave they take, which is at their own discretion, although the payments stop after a maximum of 39 weeks.

It’s a difficult decision for any self-employed worker to make – can I afford to take time off and accept what is likely to be a much lower maternity allowance payment?

There are other challenges too. A pregnant woman can usually continue to work in her role for a number of weeks safely and without complication – and there’s the incredible story of Serena Williams winning the Australian Open while carrying her first child.

But for those playing contact sports, obviously there is a need to stop playing as soon as the pregnancy is confirmed – requiring them to take a longer period of leave from their sport.

FIFA didn’t even have a standardised maternity policy until 2021, and even then it was titled as the rather uninviting ‘Minimum Labour Conditions for Players’. Under this legislation, players are allowed at least 14 weeks of maternity leave – receiving 66% of their salary during that time.

It should be noted that this is the minimum terms of maternity for football associations operating under FIFA’s remit – some, including the FA in England, have chosen to go above and beyond that.

Tennis’ Big Freeze

All sport should be a meritocracy – the best should be given a pathway to the top based upon their performances. But in individual sports where success is governed, by and large, by a world rankings system, which in itself is governed by players racking up wins on a consistent basis, what happens when a self-employed player takes themselves off on maternity leave?

Their lack of activity sees them tumbling down the rankings, which in tennis means that they have to hope they are given wild cards on their return to the court – if not, they will have to battle through several rounds of qualifying just to reach the first round of a Grand Slam; simply because they decided to start a family. In 2018 Serena Williams, arguably the greatest women’s player in history, saw her world ranking drop to 453 as a result of her time away.

This was clearly an inadequate policy, and so the WTA in 2018 finally moved to make amends, effectively ‘freezing’ the world ranking of players that fall pregnant and take some time away from the tour.

Protected Rankings in Tennis

The new Special Ranking rule allows players to enter up to 12 tournaments in a three-year window using their ranking at the time they went on maternity leave – meaning that they could enter the main draw of Grand Slam events.

At the 2024 Australian Open, former major champions Naomi Osaka and Angelique Kerber entered the first round via their protected rankings after giving birth to children in the months prior – enriching the tournament with their presence, which is what makes the WTA’s system such a breath of fresh air.

But could they do more, by guaranteeing their players maternity pay?

This is the other elephant in the room of what is, essentially, a self-employed sport. The WTA has no legal obligation to offer maternity pay to its players, but there are plenty within the sport who believe they should.

“I think it would definitely be life-changing and I feel like having a kid shouldn’t feel like a punishment,” Osaka has said.

Victoria Azarenka, meanwhile, is another top player who took time away from tennis to start a family.

“I have, I’m guessing, more financial security than some players who may be outside the top 100, and maybe have the same desires and ambitions to have a child and continue to do their job,” she said.

And that is perhaps the key point. The likes of Osaka, Azarenka and Kerber have enjoyed fine careers and won plenty of prize money – that’s not to say they don’t deserve maternity pay, but at least they have a level of financial security. But what about lower-ranked players considering starting a family?

Tatjana Maria and Taylor Townsend are just two players that took a ‘gamble’ in taking a leave of absence from the sport – not that raising a family should ever feel as such. Maria was ranked 258 in the world when she decided to start a family in 2013, having never gone beyond the second round of a major. Had she not come back stronger, pregnancy could have ended her career from a financial perspective.

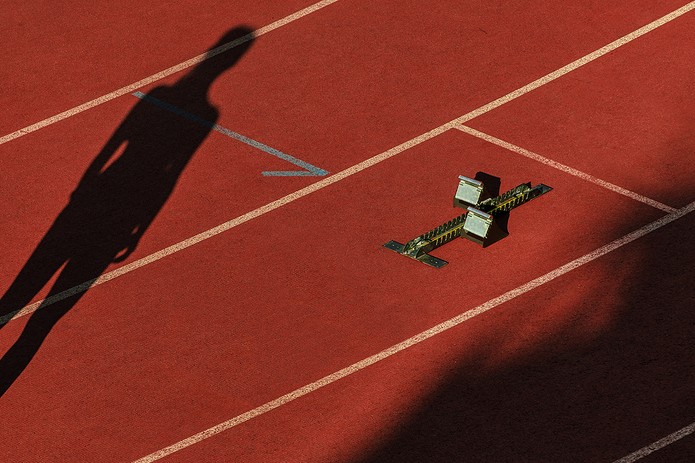

Left Behind on the Track

If you thought the financial situation in tennis was questionable, how about that of track and field athletics?

The prize money in athletics is a lot lower than in tennis, and to make matters worse athletes do not get paid to represent their countries – not even at the Olympic Games, although there does tend to be a bonus structure in place for those that win a medal.

Sprinters and long-distance runners also have to be mindful that they may not be able to compete at the same high level after giving birth – there’s medical evidence to suggest as much. But there are anomalies, with the likes of Allyson Felix, Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce and Shaunae Miller-Uibo continuing to excel on the track as mums.

Miller-Uibo, at least, is a commercial dream – her outgoing personality and brightly coloured hair marking her out as the kind of athlete that brands love….the fact that she’s damn fast over 200m and 400m, a two-time Olympic champion in the latter, also helps.

The Bahamian has penned commercial deals with Adidas and others, taking away some of the financial pressures of taking time off to give birth to her first child.

But for others? There’s no such luxury. Indeed, Felix has revealed that Nike wanted to enforce a 70% pay cut after she got pregnant, and would refuse to guarantee fees if she did not perform ‘at the highest standard’ upon her return to the track.

Unsurprisingly, Felix left Nike thereafter, with the brand subsequently overhauling their maternity policies after others came forward – Kara Goucher was forced to run a half-marathon just three months after giving birth because Nike had threatened to cease payments to her until she started competing again. She claimed she made ‘more than a dozen’ unpaid appearances for the brand.

This isn’t meant to be a slam dunk on Nike, who ironically sell a range of maternity clothes, but just an example of how and why women are putting off pregnancy for financial reasons – or jeopardising their careers by getting pregnant in the first place without an adequate maternity pay system in place.

What is the Rule on Maternity Pay in Sport?

As far as team sports are concerned, there’s no hard and fast rule on how pregnant athletes will be supported.

The Football Association, going above and beyond FIFA’s barebones approach, has implemented a rule in which a contracted player will be paid 100% of their weekly wage by her club for the first 14 weeks of maternity leave – higher than FIFA’s 66% requirement.

French football had stuck with FIFA’s minimum obligation – until Lyon were taken to court by their former captain Sara Bjork Gunnarsdottir, who argued that she should be paid her full wage for the first 14-week term.

A FIFA tribunal agreed – forcing Lyon to make a retrospective payment on her unpaid salary.

“The victory felt bigger than me. It felt like a guarantee of financial security for all players who want to have a child during their career,” the Icelandic international said.

“I want to make sure no one has to go through what I went through ever again.”

Rugby, and specifically the RFU, has watched the complications faced in other sports and delivered a maternity policy that is fair, progressive and ensures that expectant players have every chance to thrive during their pregnancy and return to the pitch after it.

They offer 26 weeks of fully paid maternity leave – almost double the minimum standard in football, and a package more in-line with the standard workplace in the UK.

Not only that, the RFU also pay for the travel and accommodation of the children in their first 12 months of life, which affords new mums a chance to travel with their teammates and feel part of club life even while out of action.

And, perhaps most crucially, there’s contractual protection too. If a player’s contract is due to be renegotiated or extended at any point during their pregnancy or maternity leave, there will be an automatic extension of 12 months – no questions asked.

“I’m confident the policy will help normalise motherhood in sport and give players the best possible chance of returning to play should they wish to do so in a secure and safe way,” said Abbie Ward, the England international who herself announced her pregnancy in 2023.

Here’s hoping that other sports will ultimately choose to follow rugby’s lead….

Do Female Athletes Perform Better After Pregnancy?

One of the misconceptions about pregnancy in sport is that an athlete may never return to previous highs.

But there’s nothing to stop them from doing so, while many report a greater sense of perspective and passion to win with their child or children watching on from the sidelines.

Margaret Court, Evonne Goolagong and Kim Clijsters all won Grand Slam tennis events after childbirth, while Serena Williams reached four major finals. Elina Svitolina, who only returned to action in 2023, has already matched her best efforts at the French Open (quarter-final) and Wimbledon (semi-final) since giving birth.

There was an amazing stat at the 2023 New York Marathon: six of the top-ten finishers were mothers, including Jessica Stenson, who won gold at the Commonwealth Games after giving birth. Sinead Diver, another Aussie marathon runner, set a national record as a parent.

And the research seems to stack up, too. One research study found that ‘most athletes felt that their performance level was the same or better after becoming mothers’, while others reported that their rest period actually allowed pre-existing injuries and ailments time to heal – time they might not have had the luxury of having otherwise.

Do Male Athletes Get Paternity Leave?

There’s many examples of male athletes missing games/events to attend the birth of their child.

But in the days after the birth, there’s almost an expectation that they will return to work immediately. So isn’t there statutory paternity leave in sport?

The answer is….complicated. The Athletic got their hands on a copy of the standard players contract in professional football in England – a 15-page document that outlines a myriad of rights and responsibilities.

But there is no single mention of paternity leave in the contract, and while a club would have to grant such a request if it came – that’s statutory law, but it’s felt that such a thing would be frowned upon by management and teammates….hence, there’s very few examples of paternity leave being taken in the professional game.

Over in America, Major League baseball star Daniel Murphy took three days of paternity leave in 2014 – the maximum amount his contract allowed for. Murphy himself revealed he had been lambasted for his decision, which perhaps explains why so few other players have opted to take time away from their sport.

That sort of attitude is long standing. When three England cricketers – Jimmy Anderson, Graeme Swann and Paul Collingwood – all opted out of international duty within months of each other to attend the birth of their children in 2010-11, former international bowler turned pundit Bob Willis was apoplectic.

“I don’t agree with the Mothercare buggy-rolling thinking that modern man has. He should be on the cricket tour, that’s his job,” Willis said of Anderson.

So it’s evident that there’s a long way to go before mums and dads are truly accepted in professional sport.