You don’t need to be a writer blessed with Shakespearean prose to write headlines about British tennis players at the Grand Slam events: disappointment, crashed out and early exit are just some of the descriptors that can be wheeled out on an annual basis.

You don’t need to be a writer blessed with Shakespearean prose to write headlines about British tennis players at the Grand Slam events: disappointment, crashed out and early exit are just some of the descriptors that can be wheeled out on an annual basis.

An early exit from the 2024 Australian Open left Andy Murray pondering the end of his career, while there were also disappointing losses for Emma Raducanu and Jodie Burrage.

Those were followed by defeats for the number one ranked British woman, Katie Boulter, and Jack Draper, who crashed out of the Australian Open prematurely.

Other Brits advanced beyond the second round in Melbourne, but once again it was a rather poor return from one of the best-funded tennis-playing countries on the planet – more on that later.

So why doesn’t the UK produce more elite talents in tennis? The answer, as you probably suspect, is complicated.

Diminishing Returns

Tennis changed forever in 1968 with the introduction of the Open Era: a new landscape for the sport in which professionals and amateurs could compete against each other on a level paying field.

Prior to that, there had been an almighty division in tennis – one that actually served British players rather handsomely. Before the Open Era, the likes of William Renshaw, Laurence Doherty, Fred Perry (yep, the clothes guy), Lottie Dod and Dorothea Chambers were just some of the Brits to rack up multiple Grand Slam wins in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

But the Open Era saw tennis embrace a new global age, and since then the number of British tennis champions has started to dry out considerably. Ann Haydon-Jones was able to continue her dominance after the new way was introduced, winning Wimbledon in 1969 and reaching the final of the French Open that same year.

Sue Barker, erstwhile television presenter, was also a quality player in her day, winning the 1976 edition of the French Open, while a year later her future BBC colleague, John Lloyd, reached the final of the Australian Open.

And the reign of one of the finest British women’s tennis players in history, Virginia Wade, brought with it a US Open title in 1968, an Aussie Open in ’72 and Wimbledon in 1977.

But into the modern era, and the pickings have been rather slimmer. Greg Rusedski reached the 1997 US Open final, while Andy Murray did his best to thrive in an era that has unfortunately pitched him against Roger Federer, Rafa Nadal and Novak Djokovic – three of the greatest players of all time.

Even so, Murray has won three Grand Slams – he would have surely clinched many more in a different era – and reached the final of eight others.

And then we had Emma Raducanu’s breakout success in 2021. She won the US Open as a teenager while ranked 150th in the world – a remarkable achievement and one unlikely to be matched by a similarly-unfancied player any time soon.

All told, British players have won four Grand Slam titles between since 1977 – a staggeringly meagre return when you consider the level of sporting investment in the UK compared to many other countries around the world.

Major Underachievement

As you may know, professional tennis players are essentially self-funded – they attract sponsorships, sign equipment deals, agree commercial partnerships and win prize money, all in a bid to keep the show on the road.

But at grassroots level and for youngsters with ambitions of turning pro, there is an emphasis on the bank of mum and dad – with other sporting bodies required to provide the infrastructure via which tennis can grow and players develop.

Sport England and the Lawn Tennis Association (LTA) haven’t always seen eye to eye on the level of funding required to boost the sport. Indeed, the amount shared by Sport England and the LTA has been up and down like a yo-yo over the years.

In 2012, their relationship reached a nadir – with the LTA unable to prevent falling participation figures at the local level (25% of casual players walked away from tennis in the three years prior), Sport England decided to cut their funding by a mammoth £530,000.

But even as far back as 2012, Sport England handed the LTA an annual stipend of around £6 million to fund tennis at all levels, and a decade later the LTA and the UK government joined forces to pledge £30 million to upgrade many of the 4,500 public tennis courts in England, Scotland and Wales.

And in 2022, the LTA received an additional £10 million of investment on top of their annual handout from Sport England.

That was likely in a bid to cash in on the Raducanu effect – a desire to get more women and girls into tennis, but no matter how cynically you look at the subject, there’s no doubt that British tennis is well funded….even if the results out on the court in the biggest tournaments don’t reflect as such. For context, former British pros Anne Keothavong and Laura Robson received £48,000 a year from the LTA as ‘Team Aegon’.

Comparing the funding of British tennis with their counterparts in, say, the United States, Russia or other tennis-loving nations such as Spain isn’t easy, because the numbers aren’t readily available to the public.

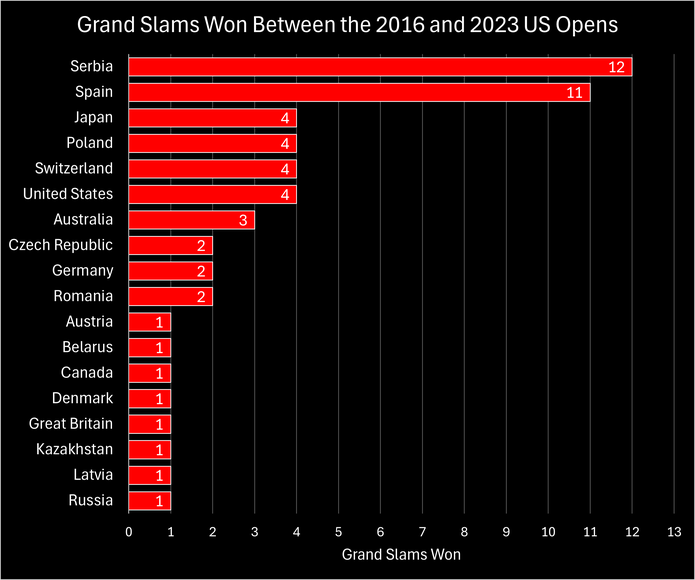

But when you look at the list of men’s and women’s Grand Slam winners since Murray triumphed at Wimbledon in 2016, it would be incorrect to suggest that British tennis is less-financed than some of the nations that appear on the list:

It would be rather far-fetched to suggest that the tennis programmes and infrastructure of Kazakhstan, Latvia and Romania are better financed than those of the UK, which confirms that British players have everything they need to be a success on the international stage – perhaps suggesting that champions are born, not made.

Indeed, when Team GB lost a Davis Cup tie against Lithuania in 2010, an investigation by The Independent newspaper found that the LTA had an annual budget of £59.7 million compared to the £90,000 of the Lithuanian tennis federation. For context, then LTA CEO Roger Draper earned an annual salary of £640,000….

Besides which, there are some things about British culture and the area’s unique climate that no well-meaning tennis coach or administrator can do anything about….

A Touch of Class

Tennis in Britain has an image problem.

It is still largely perceived as a middle class sport – a perception not aided by the Pimm’s quaffing, designer suit wearing brigade that turn out at Wimbledon’s Centre Court each year which, let’s face it, is perhaps the only time that armchair viewers will watch tennis on TV.

While cricket, that other bastion of middle-class sporting pedigree, has managed to shake off its blue-blooded history – although participation is down at grassroots level, there’s still some 2.6 million or so people that play each season in the UK – tennis has not been so fortunate.

With privilege often comes money – and as a parent or guardian, you will need lots of it to ensure that a child has the opportunity of the best tennis education. Burrage, the world number 102, has revealed that even at the age of 14, her parents were paying £25,000 a year or more to help her get the best coaching and fund travel to and from events; that’s on top of grants and subsidies handed out by the LTA.

Privilege and private education are a running theme in British tennis. Burrage attended the very selective Talbot Heath Boarding School in Bournemouth, while her contemporary Raducanu was schooled at the equally-salubrious Newstead Wood School. Even Virginia Wade’s privileged upbringing included stints at selective schools in England and South Africa, while Tim Henman too was privately educated and even had a tennis court in the back garden of his childhood home.

If these are conditions it takes to raise a quality tennis player in the UK, is it any wonder that the talent pool has been so small? Especially as any working-class child with an aptitude for the sport faces a number of restrictive barriers to entry just to get a game in.

You could even argue that Andy Murray had a privileged upbringing – albeit in a different sort of way. His mum, Judy, is a tennis nut; herself a keen player but also an elite coach. Andy had a tennis racket in his hand by the age of three, natural sporting ability coursing through his veins given that his maternal grandfather was a professional footballer.

Even with a more humble, if no less talented, upbringing, Murray enjoyed financial privileges – at the age of 15, he was sent to the Sánchez-Casal Tennis Academy in Barcelona, enabling him to play more tennis (thanks to the warmer climate) and gain an education of the clay court game.

The cost to his parents? £40,000. It’s safe to say that if you’re not from a monied family, your chances of making it as a professional tennis player are a heck of a lot slimmer.

Whatever the Weather

Other sports, like football, are so deeply ingrained in society they will never not be popular, but for tennis it seems to be a case of out of sight and out of mind for the average Joe and Jane – Wimbledon being their only engagement with the sport all year long.

That tournament, of course, is tied in with the British summer, a season which remains as unpredictable as ever in the weather it supplies. With so few indoor facilities in the UK, the window of opportunities for youngsters to get outside and try tennis pretty much lasts from June-September – barely enough time to have a decent stack of lessons or just hit a few balls.

Of course, it would be foolhardy to suggest that tennis brilliance is linked to the weather – the surplus of Grand Slam winners from Eastern Europe is testament to that. But in many of those nations, tennis is the sole summer sport played; there’s no competition from cricket and the like.

The French Open makes up 25% of the Grand Slam calendar, and it’s no secret that warm countries – which are able to host clay courts – produce more winners of this tournament than any other.

Aside from the freakish Djokovic, between 1997 and 2023, the winners of the men’s singles title at the French Open hailed from:

- Spain – 17

- Brazil – 3

- Switzerland – 2

- Argentina – 1

- United States – 1

The average summer temperature in Spain exceeds 30°, while Brazil (27°), Argentina (24°) and Switzerland (mid-20s) are hardly any cooler. Even the sole American winner during that span, Andre Agassi, hails from the sweltering Nevada desert.

In the women’s singles, the two countries that have yielded more French Open champions than any other in the Open Era are the United States and Australia. So heat, and access to clay courts as a youngster, are evidently key to success at Roland Garros.

Tough at the Top

Let’s imagine that you’ve beaten the odds: you come from a well-heeled family, live in the right place and have a bloodline of sporting success. You can make it as a British professional tennis player.

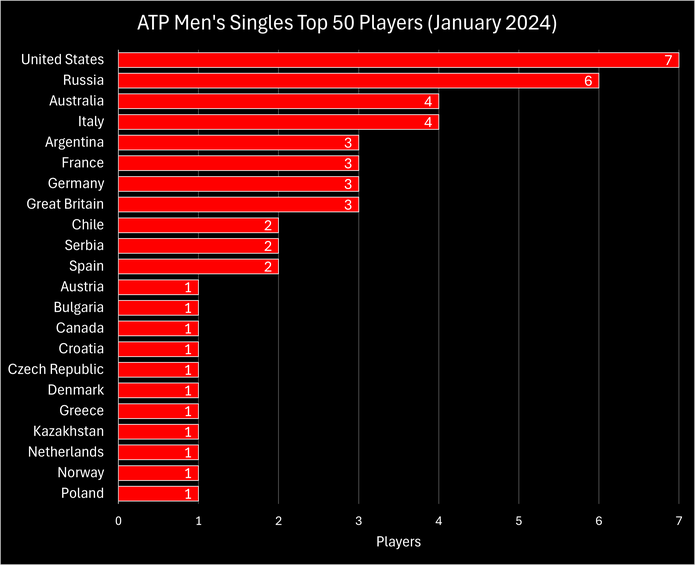

You might think that the UK’s parlous record of producing top tennis talent precludes them from making it in the sport, but that’s not actually the case: here’s a look at the countries producing the top 50 players in the ATP rankings as of January 2024.

Yes, there’s an anomaly here: the UK is not a single country and Andy Murray (one of the UK’s three players listed alongside Cameron Norrie and Dan Evans) is Scottish. But you get the general idea.

Only four nations – Russia, the USA, Italy and Australia – currently have more players inside the ATP top 50 than the UK. The takeaway point? Britain does produce elite male tennis players who can mix it with the very best.

But the diagnosis is not so good for the women’s game. The highest ranked player, Katie Boulter, sit 54th in the world – the only Brit in the top 100 of the WTA. Raducanu, her young career decimated by injuries, is well outside that elite echelon.

Some have pointed the finger of blame at the LTA, claiming that their youth scholarship funding is focused on too few individuals. Evans, no stranger to speaking his mind, has said:

“They’ve [LTA] been lucky that they had a grand slam champion [Raducanu] and she’s a very good tennis player, but the rankings don’t lie, do they? Men’s or women’s, the rankings don’t lie.

“Argentina got 12 men in the qualis here [French Open, 2023], they have no money, they have nothing. Not a federation basically. We need to make people love tennis, get involved, but if you’re putting five people on PSP [the player scholarship programme], what does that hope for the others?”

Money, money, money. It’s amazing how much of it is needed to fashion a British star in tennis, yet players from countries like Argentina, Latvia and Kazakhstan flourish without it. Makes you wonder, doesn’t it?