Hollywood scriptwriters use a storytelling arc called the ‘Hero’s Journey’ as a way of hitting the key emotional plot-points in a Box Office smash.

Hollywood scriptwriters use a storytelling arc called the ‘Hero’s Journey’ as a way of hitting the key emotional plot-points in a Box Office smash.

It’s a vehicle that has lent itself perfectly to sports movies over the years, with everything from the Rocky franchise to Field of Dreams using the Hero’s Journey as the core of its narrative.

There’s been no shortage of tennis movies made for the big screen, with this sport in particular tapping into the central themes of the Hero’s Journey: the desperation for success, the sacrifice, the obstacles (injuries, relationships, pushy parents etc) and the emotional pay-off of ultimate glory or despair.

Tennis is a remarkable sport, in many ways. It’s not prejudiced against nationality, age (relatively speaking), height or personality type – everyone has a chance to make it to the top if they have that luxury triumvirate of natural talent, hard work and a slice of luck.

Some will try to take a shortcut to the top of the sport, too. Doping in tennis has become such a problem that there’s an entire Wikipedia page devoted to it – that has around 100 individual entries of professional players that have been embroiled in doping scandals, be it inadvertent or otherwise.

Whenever the Average Joe or Jane hears that a player has been charged with a doping offence, they often immediately think of the word ‘cheat’ – that the individual has embarked on a journey of performance enhancement knowingly – in some cases, that’s been proven to be true.

However, there’s ‘accidental’ doping too – players taking medicines or supplements containing banned ingredients, with no real intent to gain a physical advantage over their opponents.

Unfortunately, these players are treated in much the same way as those who have purposely cheated, which really does beg the question: does tennis have a problem with drugs?

What is Doping in Tennis?

When we think about doping in sports like weightlifting, we may have mental images of steroid-enhanced powerhouses able to achieve physical feats the like of which the average, non-juiced person can only dream of.

But in tennis, the reality is rather different – the physical gains are not as visibly obvious for those that have deliberately cheated, while there’s likely to be no discernible evidence at all for those that have doped inadvertently.

There’s a combined anti-doping initiative in tennis that involves the sport’s leading regulatory bodies – the International Tennis Federation (ITF), the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) and the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA), who work alongside the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) to come up with a framework for policing drug use in tennis (the World Anti-Doping Code), as well as publishing a list of banned substances.

There are five general classifications of substances that are expressly banned from use in tennis. These are:

- Anabolic steroids

- Beta-2 agonists

- Diuretics

- Peptide hormones

- Stimulants

Each of these can enhance the player’s performance in a number of different ways, from building or relaxing muscles to diet management and speedier recovery times.

Tennis’ individual governing bodies have collectively handed over the running of the sport’s Anti-Doping Programme to the International Tennis Integrity Agency (ITIA).

All professional tennis players worldwide must adhere to the programme, regardless of the tour that they play on.

Do Tennis Players Get Drug Tested?

The ITIA has been handed the power to manage and implement a ‘Whereabouts’ regime of drug testing as part of their Tennis Anti-Doping Programme.

This process enables the authority to run a drug testing schedule both in and out of competition, with the legal power not to have to issue advance notice to the players when they are being tested – which would, to some extent, defeat the object.

All of the players in the International Registered Testing Pool (IRTP), which includes the top 100 players in both the men’s and women’s year-end rankings, must abide by these ‘Whereabouts’ rules – three non-compliances, which is loosely described as a failure to fulfil testing policy, can lead to an anti-doping rule violation (ADRV) being recorded….with a sanction to duly follow.

The ITIA’s motto is that ‘any player can be tested any time, any place’ – be it at a tournament, outside of the season or even via an impromptu visit to a player’s home.

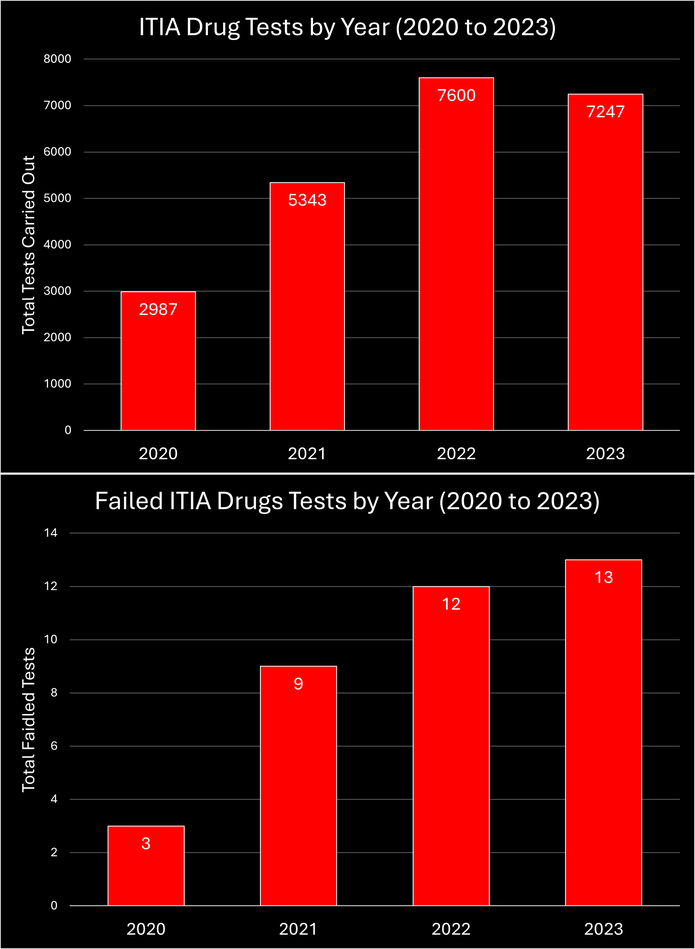

The charts below confirm the extent of the ITIA’s testing regimen, with a marked drop-off in 2020 due to the global health emergency:

The upshot is that the more tests that are performed, the more dopers that are caught.

There have been accusations that the ITF has falsified the number of tests that it has sanctioned – allegedly over-counting to pump up their figures, while it’s also claimed that some players were allowed to select their own time and location for so-called ‘random’ testing.

The ITIA reports on the number of tests it performs each year, but also the players involved and the frequency with which they are tested. Because of the random nature of their testing schedule, the differences between individuals can be stark.

For example, in 2022 Novak Djokovic was tested in eight of the first eleven tournaments that he played. Garbine Muguruza, meanwhile, was tested in just 5/19.

That’s not to suggest that Muguruza has done anything wrong – it’s just further evidence of the inconsistencies, and possible discrepancies, that can arise from such a randomised process.

Historically, the ITF has only committed a miniscule budget to anti-doping testing – around $7 million a year historically. The winner of the U.S. Open takes home $3 million, for context, which shows the preposterousness of the lack of resources given to fighting doping in tennis.

What is the Punishment for Doping in Tennis?

There is a wide-ranging selection of sanctions available to tennis’ governing bodies for players that fail a drugs test and are, therefore, classified as doping.

Disqualification from Past Tournaments

The first is that the player will suffer from a retrospective disqualification of their results, which will see ranking points earned taken away and, potentially, even a title win if the individual is charged with a doping offence for it.

Prize Money Repayment

As if disqualification wasn’t enough, they may also be forced to repay any prize money won from events in which their participation was tainted – there’s even scope that they have to repay the earnings of any doubles partner that is proven to be clean but is later disqualified.

Suspension

A number of players have been hit with bans courtesy of their doping misadventure – we’ll have a rogue’s gallery of those later in this article. These suspensions can range from the temporary to a lifetime ban from the relevant tour.

When the banning order is temporary, a player will be left kicking their heels on their sidelines – they will, compared to the others on their tour, be losing out on ranking points, which can in turn see their overall ranking fall; making it harder to secure qualification for the Grand Slams and other significant events on the tours.

Loss of Sponsorship & Damage to Reputation

The ITIA also lists a raft of other ‘punishments’ that while, human in nature, are no less damaging to the individual. Reputations can be permanently tarnished, which in turn affects future earning potential – sponsorships and commercial deals are likely to be lost if you are outed as a drug cheat.

Media coverage, in the digital age, is forever – news stories don’t simply disappear online, as might have been the case of the years gone by of print-only media.

Who Has Been Caught Doping in Tennis?

In amongst the players that have been caught doping in tennis, there’s a small handful of Grand Slam winners – the pinnacle of the sport.

Amongst the most famous was Andre Agassi, who produced a positive test for methamphetamine in 1997. The eight-time Grand Slam winner claimed a drink of his had been spiked, although much later admitted in his autobiography that he had become addicted to the drug. He served a ban of just three months.

Marin Cilic, the former US Open champion, produced a negative when Nikethamide was found in his blood in 2013. A drug that stimulates the respiratory system, the Croatian claimed he had inadvertently come into contact with it via glucose tablets purchased in France. Cas took his side, with a ban of just four months served.

Petr Korda, the 1998 Australian Open champion, tested positive for Nandrolone that very same year. He had his Wimbledon prize money and ranking points revoked, before announcing his retirement from the sport before his suspension was enacted.

And Martina Hingis, the five-time Grand Slam winner, was effectively forced into retirement after being found guilty of taking Benzoylecgonine, a trace of cocaine. She was banned for two years, forfeited her world ranking and was fined in the region of £100,000. The ITF would not hear her appeal as she had already retired from tennis.

What is Inadvertent Doping?

Although there’s only five categories of banned substances, the actual list of individual doping agents runs into the hundreds.

So there’s a challenge for the players: to check any medicines or supplements they use for active ingredients that feature on the banned list.

The ITIA have reported on several instances of ‘inadvertent doping’, in which the player has used medicines or supplements that are widely available – but which contain banned substances.

So even though the player has made no attempt to gain a competitive advantage from their medicines and supplements, they have been caught out and subjected to the sanctions available to the ITIA.

Kamil Majchrzak

Kamil Majchrzak has played in Grand Slams and represented Poland at the Olympics, but his life came crashing down when a drug test revealed the presence of an anabolic steroid.

He was later able to prove that a supplement was contaminated – the ITIA confirmed as much by testing unopened sachets of the herbal nutritional drink, but the Pole had already missed a year of his career while serving a ban; only to be exonerated, with no compensation forthcoming.

Maria Sharapova

The situation is made all the more challenging given that the list of banned substances is fluid and ever-changing, with new additions being introduced regularly.

That could have cost Maria Sharapova dearly. The five time Grand Slam champion was allowed to use Meldonium, a substance used to treat her diabetes symptoms and magnesium deficiency.

But this would latterly be added to the list of banned substances without the Russian’s knowledge, hence her failed drugs test of 2016 when she played at the Australian Open just days after the rule change.

Her two-year ban – the ITF putting the blame at her door for not checking the new list of banned substances – was eventually reduced to 15 months, when Sharapova and her legal team went to Court of Arbitration for Sport (Cas) with their frustrations.

Tara Moore

The plot thickens yet deeper. In some countries, farmers and livestock producers use a form of steroid to boost the growth of their cattle. So even consuming meat can lead to anabolic steroids or metabolites appearing in a player’s urine sample – leading to some awkward questions to be answered. In Tara Moore’s case, it cost her nearly two years of her career.

— Tara Moore (@TaraMoore92) December 23, 2023

The situation is so potentially damaging that players have even been warned against eating meat produced in countries such as China and Mexico, while instructions are in place for players to only eat at tennis federation-approved restaurants and eateries.

Simona Halep

The LTA expressly states that their players must ‘take responsibility for what you ingest’, which must be an exhausting way to have to live your life.

It’s a credos that the sport’s governors have lived by, although the intervention of Cas in a number of cases has enabled the player to enjoy a reduction in their ban after a conclusion of ‘inadvertent doping’ was delivered.

Such a result saved the career of Simona Halep. She was initially banned for four years in 2022 after a test found she had Roxadustat in her blood – a substance known to increase the production of red blood cells in the body, which in turn promotes stamina maintenance and recovery.

But Cas would hear the appeal of Halep’s team, before deciding that the Romanian was contaminated by a legal supplement containing the substance. Her ban was reduced to nine months.

Halep plummeted down the WTA rankings during her absence, which meant that she had to rely on tournament wildcards upon her return – a somewhat unfair situation, perhaps, given that she was ranked inside the top-10 in the world at the time of her suspension.

Richard Gasquet

Other substances on the banned list include recreational drugs, which evidently offer no performance-enhancing qualities but are prohibited nonetheless. And one of the highest profile episodes of ‘doping’ in tennis was Richard Gasquet’s ‘Cocaine Kiss’ controversy of 2009.

The Frenchman, in his downtime, found himself canoodling with an admirer in a Miami nightclub. Unbeknown to him, the lady in question had taken cocaine that evening – traces of which found its way into Gasquet’s system.

After a failed drugs test, which saw the ITF initially issue a two-year ban, Gasquet appealed the decision and saw the suspension first reduced to one year before being quashed altogether by Cas.

Although he only missed six weeks of action, all told, Gasquet was forced to sit out the French Open and Wimbledon in 2009 while his case was heard – resulting, potentially, in a considerable loss of earnings.

Given the reduction in numbers of players openly admitting to doping, maybe tennis’ true drug problem is in proving whether or not an individual that does deliver a positive test was in on it all along – or unluckily caught up in a situation not of their doing.

And with the precedent set by Cas, it will be much harder to make allegations of improper substance use stick.